Understanding heat

In extreme heat, recognizing environmental stressors, understanding how your body responds, and allowing time for acclimatization can help support better performance and decision-making. Whether you’re on a sports field or out for a summer jog, building awareness is the first step toward smarter training in the heat.

overview

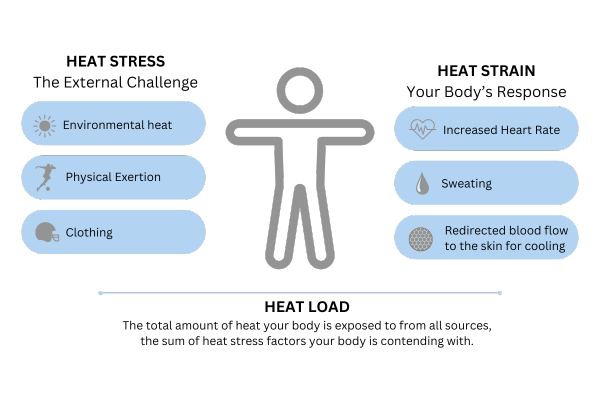

Understanding Heat: Heat Stress, Heat Strain, and Heat Load

Picture a day when you're exercising or playing a sport in the sun.

The combination of heat, humidity, and physical effort creates heat stress—the environmental challenge.

Your body reacts through heat strain—sweating, increased heart rate, and working hard to stay cool.

When this demand builds over time, it becomes heat load—the total burden on your body from heat exposure, exertion, and insulation.

Learning how your body responds to heat is the first step toward smarter training decisions in hot environments.

Explore How HeatSense Tracks Heat Response

Heat Load Defined

Heat Stress: The External Challenge

Heat stress refers to the environmental and external factors that make it harder for your body to stay cool. These include:

- High air temperature, humidity, and sunlight

- Intense physical activity

- Clothing or gear that traps heat

Think of heat stress as what the environment is doing to your body.

Heat Strain: Your Body’s Response

Heat strain describes how your body responds to heat stress. This includes:

- Sweating

- Increased heart rate

- Shifting blood flow to the skin

Your ability to manage heat strain depends on thermoregulation—how well your body maintains internal balance. Factors like hydration, fitness level, and prior heat exposure all play a role.

Heat Load: The Cumulative Demand

Heat load is the total amount of heat your body experiences—from the environment, your own activity, and what you're wearing.

It’s the sum of all stressors your body has to manage to stay in balance.

your body reacting to heat

Acclimatization: Adapting to Heat

Acclimatization is your body’s natural adjustment process to heat. With regular, gradual exposure, your body can:

- Sweat more efficiently

- Regulate internal temperature better

- Maintain better fluid and electrolyte balance

Most people begin to acclimatize within 7–14 days of consistent activity in hot conditions.

Heat Illness: When Strain Escalates

When the body’s ability to cope with heat is overwhelmed, it may lead to heat-related symptoms. These include:

- Heat rash: Skin irritation from sweating

- Heat cramps: Muscle cramps due to fluid or electrolyte loss

- Heat exhaustion: Dizziness, nausea, fatigue, and heavy sweating

- Heatstroke: A severe condition where the body’s core temperature rises dangerously, requiring urgent cooling

These effects are often associated with sustained heat load, dehydration, and insufficient recovery time.

Hyperthermia: When the Body Overheats

Hyperthermia is a term used to describe an unusually high body temperature that results from the body’s inability to effectively cool itself. It is associated with various heat-related conditions, such as heat exhaustion and heatstroke, which can arise when thermoregulation is compromised by prolonged heat exposure or physical exertion.

Frequently Asked Questions

Heat stress is what the environment does to you—the combination of air temperature, humidity, sunlight, physical activity, and clothing or gear that makes it harder for your body to stay cool. Heat strain is how your body responds to that challenge through sweating, increased heart rate, and redirecting blood flow to your skin. Heat load is the cumulative total—the sum of all heat stressors (environmental conditions, your own activity intensity, and insulation from clothing or equipment) that your body must manage to maintain balance. Think of it this way: heat stress is the challenge, heat strain is your body's reaction, and heat load is the total burden over time. Understanding all three helps explain why two athletes in the same environmental conditions (same heat stress) can have completely different experiences—their individual heat strain and accumulated heat load may be very different based on fitness, acclimation, hydration, and other factors.

Most people begin to acclimate within 7-14 days of consistent activity in hot conditions, but individual adaptation rates vary considerably. Signs that you're becoming heat acclimated include: sweating starting earlier and more efficiently during activity, lower heart rate at the same exercise intensity in heat, feeling less fatigued during hot workouts, and faster recovery after heat exposure. However, subjective feelings aren't always reliable—some athletes feel fine but are still experiencing elevated internal heat strain. The most accurate way to assess acclimation is through objective monitoring of your core body temperature response over time. If your core temperature rises more slowly and stays lower during equivalent workouts as you progress through training, that's evidence of successful acclimation. Without monitoring, err on the side of caution with gradual progression, and pay attention to how you feel compared to earlier sessions in similar conditions.

Individual heat response varies enormously based on multiple factors. Fitness level matters—better cardiovascular conditioning improves heat tolerance. Acclimation status is critical—someone who's been training in heat for two weeks will handle it much better than someone on their first hot day. Hydration status affects thermoregulation directly—even mild dehydration impairs your body's cooling ability. Body composition plays a role—larger athletes generate more metabolic heat, while body fat provides insulation that makes cooling harder. Recent illness, sleep quality, medications, and even genetics influence heat response.

Dehydration and heat response are intimately connected. Your body relies on sweating to cool itself, and sweating requires adequate fluid volume. When you're dehydrated, blood volume decreases, which makes it harder for your cardiovascular system to simultaneously deliver oxygen to working muscles and route blood to your skin for cooling. This means your heart has to work harder (higher heart rate) to accomplish the same tasks, and your core body temperature rises faster because cooling efficiency is impaired. Even 2% dehydration can decrease work capacity by 30% and significantly increase perceived effort. The relationship is cyclical: heat exposure increases fluid loss through sweating, which leads to dehydration, which impairs heat tolerance, which increases heat strain. This is why individualized hydration strategies are a core pillar of Heat Readiness—your hydration needs in hot conditions are highly individual based on your sweat rate, activity intensity, body size, and environmental conditions.

The content provided on this page is for general educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any medical condition. HeatSense does not provide medical advice. Always consult a healthcare provider for concerns related to health and safety.